The Beauty and the Beast board game is an ingenious engineering of cinematic, narrative and architectonic space into a slot-together cardboard allegory. A tie-in with the Disney film of 1991, players first build the Beast’s castle, condensed into the building’s ballroom (the main section of the board), staircase and tower. Its central mechanic is a revolving disc within the ballroom-board that at once drives the game, revealing characters and triggering events, and functioning as a kinaesthetic and paracinematic toy device – evoking the swirling motion of the central characters, and the virtual camera, in the movie’s baroque ballroom dance sequence (itself foregrounded in the film and its marketing as a technical and aesthetic achievement in the integration of 3D CGI with drawn cel animation).

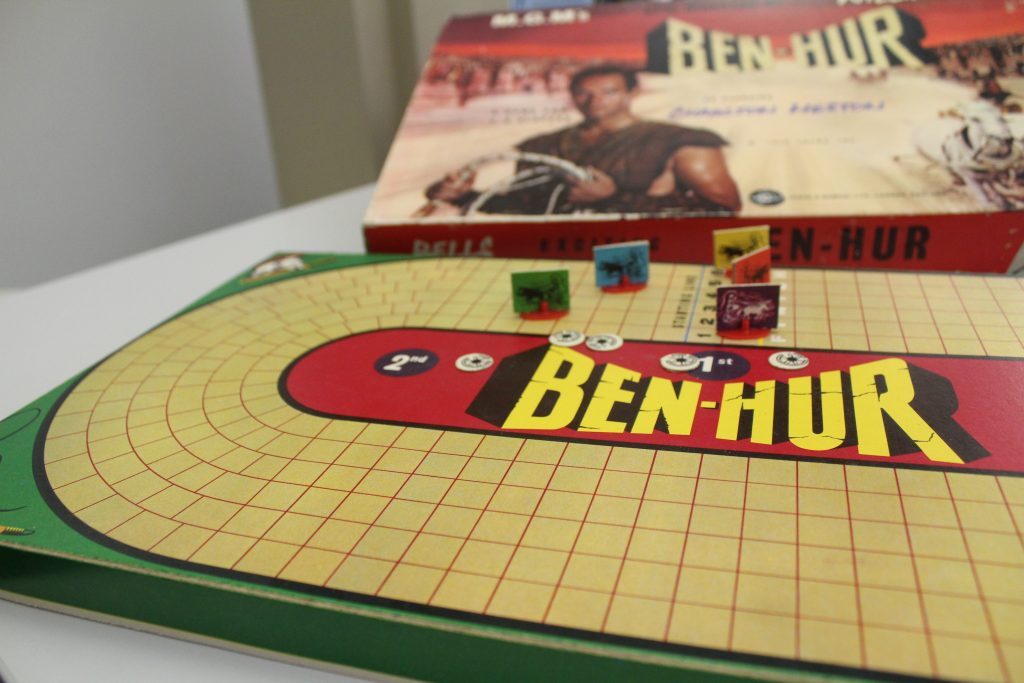

The articulation of imaginative, mimetic play with popular film and hands-on manipulation of devices was evident in many of the collection’s board games and card games. These not only capitalise on the popularity of the films and extend their action and themes into domestic play, but also transduct the action and themes into mechanical devices. The games are machines both in the sense of being structured around a game mechanic (rules, dice-throw randomisation, win-states, and so on), but also more literally as moving mechanisms. Like Beauty and the Beast, the collection’s King Kong game is particularly inventive in its translation of the filmic world into a cardboard and plastic mechanism with sliding, moving, manipulable characters and objects. The game strips the film’s action down to the culminating scene of the monster’s ascent of New York’s twin towers.[i] A Ben Hur themed game is more traditional in its structure and metonymic in theme: the board depicts the track and the tokens the chariots, from the movie’s central chariot race scene.[ii] Other board games in the Bill Douglas collection have movie industry themes, effectively simulating – albeit in a manner stylised for simple game play – Hollywood studios’ film production.[iii]

The Beauty and the Beast game illustrates nicely this chapter’s proposition that in twentieth century cinema and TV merchandising should be seen not as ephemeral or paratextual to industrial screen media, but rather as an overarching media culture of the play and construction of moving images and objects, one with its own material and technical qualities and innovations and with its own everyday imaginative realisation. I would add too, that, in its material and technical make up, this game attests to a genealogy of hands-on media play that precedes industrial cinema by centuries. In this sense its kit-like construction and then its animation of figures in a dramatic stylised world suggests a dextrous and ludic kinoculture.

Before plastic, cardboard and paper were archetypically toyetic materials: cheap and easy to produce, to cut and shape and print on – cardboard playthings were often initially produced as an offshoot of more functional products or packaging, and were often as disposable. As sheet materials cardboard and pasteboard replaced wood in board game bases, toy buildings such as houses and castles, and simple mechanical devices from punchinello or jumping jack puppets to optical toys, and cardboard toys were generally packed and distributed in kit form, to be slotted or glued together at home. Cardboard and paper offered a cheap alternative material for multiple toys such as toy soldiers and tied in with other forms of print media, such as paper fashion dolls published in girls’ comics. Papier maché has been used as a cheaper, lighter and less fragile alternative to ceramics and composition for puppets and dolls’s heads and even whole dolls such as Gelenktäufling, flesh-coloured and jointed papier maché dipped in wax to simulate human skin, exported from Germany to Britain around 1850,[iv] and instead of carved wood in toy animals and soldiers in the early German toy industry in the seventeenth century.[v] Cardboard continued through the twentieth and into the twenty-first century as a key toy material – from the ubiquitous plain cardboard box[vi] to the playful design innovations of the Eames. Google has deployed it as architecture for smartphone-based VR viewers and consumer AI kits. To the material and practical aspects of cardboard (cheapness, lightness, foldability) is added ‘makerly’ connotations for certain kinds of educational and hobbyist projects.

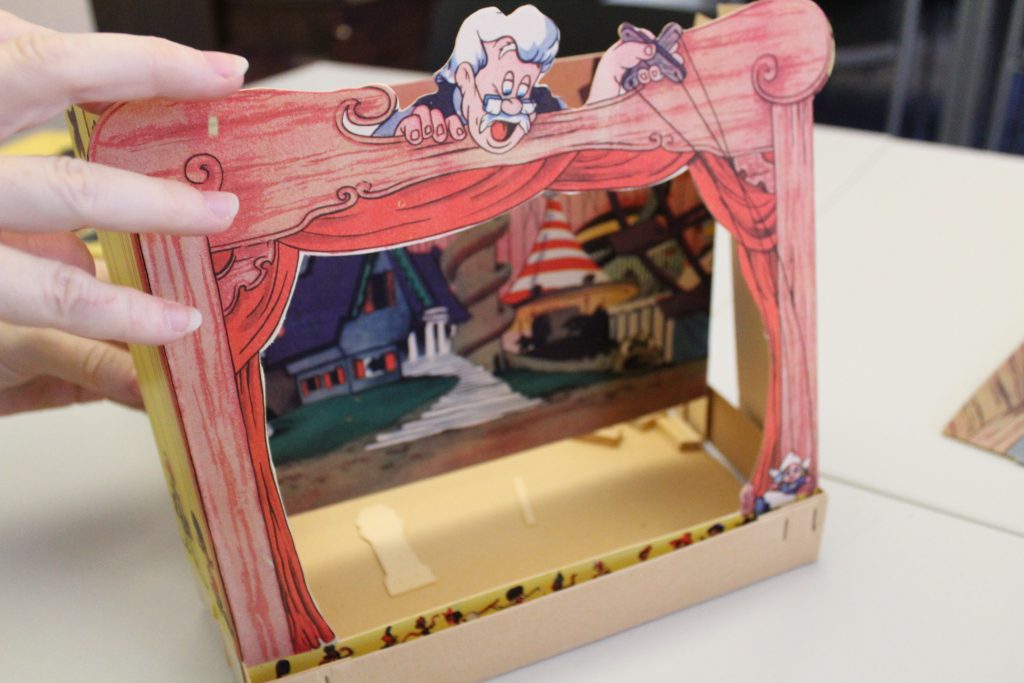

Unsurprisingly, given their industrial and formal relationships with book production, cardboard and paper toys and devices have often been constructed and folded into storytelling contexts. Since the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, toy-like and didactic paper objects for young children, have played across picture books, pop-up books, picture cards and blocks. Froebel designed colourful shaped cards to complement his wooden Gifts, and Hans Christian Andersen, as well as his conventionally published stories, created numerous drawings and cut paper versions of his characters and others from contemporaneous popular theatre. Jacqueline Reid Walsh notes that from childhood Andersen had been familiar with popular performances of toy theatres, dolls, mechanical animated pictures and drew on these forms in his paper cuts. The act of cutting out and manipulating these paper shapes reflects the coming-to-life or animation of toy objects in his stories, such as toy soldiers and toy theatres. Reid-Walsh argues that his characters, both on the printed page and in cut paper, constitute a precinematic animation:

By drawing on the movement inherent in the play realm of the toy theatre and in the plastic motion of the paper cut Andersen inserted a sense of motion into his representations of toy figures, both three dimensional and two dimensional […] the technique seems to be a visual description of an effect of pre-cinema animation constructed from a combination of these two areas of artistic production.[vii]

Ingeniously engineered books in the nineteenth century blurred the distinction between book, puppet theatre, and mechanical toy with articulated figures and animals animated through pop-up and tab-pulling mechanisms.[viii] Card and paper toy theaters themselves feature in the Bill Douglas museum, and are historically closely related to the various forms of, and overlaps between, the dolls’ house and the peepshow.[ix] They include a number of early to mid-twentieth century theatre and ballet peepshow or ‘tunnel’ ‘books’ which open up in a concertina mechanism, their cut out figures and scenery flats processing into the stage space. I toyed with the construction of a Danish set themed on Disney’s Pinocchio (1940), a set of colourful card backdrops to slot together, and sheets of figures in various dynamic poses evoking their animated movement in the film. The framing proscenium arch features Gepetto looking over the top, holding a marionette handle, its strings running down the side of the arch towards the stage in a playful condensation of the story’s themes of puppetry and agency with the toy theatre’s own invitation to the manipulation of dramatic figures.

Shadow theatres are the simplest form represented in the collection. A twentieth century set consisted of little more than a tracing paper screen and some sheets of card and fastenings for the owner to construct their own characters and action. Shadow theatre and puppetry as a sophisticated narrative and ritual medium appears around the world, particularly in India, China and South-East Asia, with the figures themselves fashioned from materials including leather and paper.[x] It seems likely that the casting of shadows of objects or the hands from the light of a fire is as old as the human management of fire itself (and is alluded to in Plato’s allegory of the cave). As well as direct technical and aesthetic connections between the toy media of shadow theatre and puppetry and industrial cinema (in for instance stop motion modes of animation, Georges Méliès’ prop-based tricks, and the films of Lotte Reiniger), celluloid-based ‘live action’ cinema is a form of shadow play as the image is formed from the passage and blocking of light through the movie frame.[xi] As a literal screen moving image medium shadow play is playful cinema in the overarching sense I am suggesting here.

As cinema in this chapter’s very broad sense then, these cardboard objects are integral to the conventional category of pre-cinematic devices, to a looser genealogy that includes peep media and dolls’ houses, and to a much broader sense of toying as a practice of animating images and figures – and of the animation of the playing child’s body. Across these perspectives lies another, and one that can be applied through to contemporary digital and postdigital kinoculture, one in which mechanical toys, in various ways, regulate time and movement (and hence connect more closely to industrial cinema): through the repetitive movements and micronarratives of the mechanical book figure,[xii] the looping imagery of the zoetrope, the rule- and turn-based procedures of the boardgame to—beyond the paper substrate now—the algorithmic microtemporalities of the robot automaton, AI and the videogame.

[i] The game is based on the 1976 remake, not the 1933 original. Paramount, dir. John Guillermin.

[ii] Ben Hur, MGM, dir. William Wyler 1959

[iii] The notion of board and tabletop games as a simulational media form is developed in more depth in Chapter 3: Toy Soldiers. In 2005, the Lionhead videogame developers released a Hollywood-themed sim The Movies.

[iv] von Boehn (2010 [1932]): 156.

[v] Von Boehn 2010 (1932) 293.

[vi] See Chapter 4: Construction Toys

[vii] Reid-Walsh 2007: 284.

[viii] Field 2019: 153-181

[ix] Disney’s multiplane camera technique, which added depth effects to the previously shallow pictorial space of cel animation (see Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1938)), uses very similar visual, perceptual and technical principles to the peep show and toy theatre (Langer 1992).

[x] Cook 1963

[xi] Herbert 2000: 11

[xii] Field 2019: 158