The first of three posts linking my recent holiday to Crete with themes from Toy Theory.

Toys as technological devices operate through two very different historical or temporal dimensions. They appear to be inseparable from the earliest artefacts fashioned by humans over tens of thousands of years ago – miniature figures of the human and the animal, bound up with ritual and ornament but with clear evidence of design for children’s play. They also attend, and shape, every individual life history nested within these millenia: different objects and mechanisms designed for, or appropriated by, children as they grow and change from infancy through childhood and puberty.

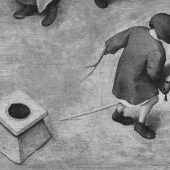

This artefact in the Archaeological Museum of Chania, Crete, appears very early on in each of these timelines. It is a figure moulded from clay between the first century BCE and the first century CE, unearthed at nearby Aptera, a site with remains of Greek temples and Roman baths and villas. It is hollow and next to it in its museum vitrine are the small clay beads found inside it. As a child’s rattle it is one example of a very old type of device, going back at least 2500 years and with its essential mechanical principles unchanged. And it is one unambiguously intended for the amusement and distraction of babies and infants. For whereas many ancient figurines are ambiguous in their original purpose – often ritual objects passed on to children, or that mix of toy and ritual use – the rattle is a little handheld device dedicated to the extension of the infant’s motor and sensory world out into phenomenal and acoustic space. Like the softer forms of transitional object, such as fragments of fabric or soft toys, these instruments mediate the child’s emergence in subjecthood, but with their hard and noisy characteristics, do so into physical and mechanical action as well.