The city is already a playground. Creative projects to turn urban spaces into playful installations or events are often predicated on the implicit assumption that the city is not already playful. That urban centres are cold, alienated places just waiting for artists, architects, designers and cultural producers to bring their creativity and imagination to bring them to life, to forge new social relationships and cooperative behaviour, to conjure up new ambiences and warm encounters, free from commercial entertainment, privatised leisure and atomised experience.

However, many cities, in the global north at least, have seen since the postindustrial decline and recessions of the 70s and 80s, a new liveliness and conviviality driven by the development of waterside areas and zones of bars, cafes, clubs and cinemas that see evenings and weekends given over to a festive spirit of social gathering, laughter and entertainment. University cities in the north of England see hordes of students in fancy dress, stag and hen dos drive a carnivalesque tourism from Dublin to Prague, whilst who knows what quiet, unnoticed cats cradles of playful interaction is being strung across the city as mobile-equipped citizens trail threads of casual games and the word-and-image play of social media.

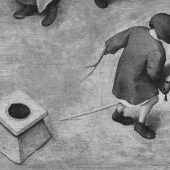

The city is already a playground even for children, though the presence of their play is less obvious and its persistence more tenuous. Still, parks and pavements are still marked by the chalk residue of hopscotch; family photographs and memories document the appropriation of city centre fountains as paddling pools, and street furniture as climbing frames. Cracks between paving stones and patches of tarmac still interrupt everyday transit down the pavement with magical power or volcanic peril. For teenagers, carparks become skateparks and bus shelters a sanctuary for the endless adolescent game of conversation.

I am not arguing that the existing city-as-playground is an ideal playful zone requiring no creative or infrastructural intervention – far from it. But by seeing it as always-already a playground we can direct critical and creative attention to existing behaviours and infrastructure, play and games that are surprisingly persistent, erupting through the concrete like flowers. Firstly so that these persistent games and microgames can be nurtured, and accentuated, in their own right, and as a resource – an inspiration for new games and playgrounds. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly – to identify and attack all the factors that limit its ludic possibilities. The regulations and policing of privatised spaces of leisure and retail, of transport, the invisible barriers of economy, cultural capital, and risk that often keep the C21st city centre a gameboard clearly zoned along the lines of social difference.

Children’s urban play in particular is corralled into tiny pockets of time and space. Childhood in the cities of the global north underwent a quiet apocalypse sometime in the mid twentieth century as the car transformed open spaces of play into an inhospitable and lethal environment.

Perhaps the most radical and far-reaching interventions we could make would be not to install new ludic techniques and technologies, but rather to systematically clear away the existing physical, social, economic and temporal obstructions to urban play, to open up spaces like the post-War bomb-sites – and leave it to children and adults to make their games in the rubble.

This modest proposal aside, I would not argue that games and playful activities created by artists, architects, and games designers be abandoned. I have conducted ethnographic studies of many such projects, and collaborated on a few. They are usually thought-provoking, innovative, and often great fun. As well as the industrial continuities of concrete and steel there are emerging postindustrial infrastructures of transit and communication, of spectacle and entertainment – all of which demand new modes of play. There is always space for new games.

Rather I would argue that such initiatives should be evaluated coolly, their claims presented modestly and with a sociological and anthropological attention to their milieu and effects. Initiatives such as Playable City would do well to read Shannon Mattern’s ‘The city is not a computer’. Though playable city imaginings are an explicit reaction to the neoliberal idealism of the Smart City imaginary, they risks replicating aspects of that which they would resist. Partly through an uncritical concept of media technological development (but that’s an argument or provocation for another day), but particularly in approaching urban space as an anthropological non-place, rather than a living playground. We need to ‘inject’ as Mattern puts it, ‘history and happenstance.’

This provocation was written for Cities as Playgrounds: new models for urban play, civic engagement and sociality, RMIT Europe, Barcelona 12-13 June 2019. Organised by Larissa Hjorth and Clancy Wilmott.

One thought on “the city is already a playground”