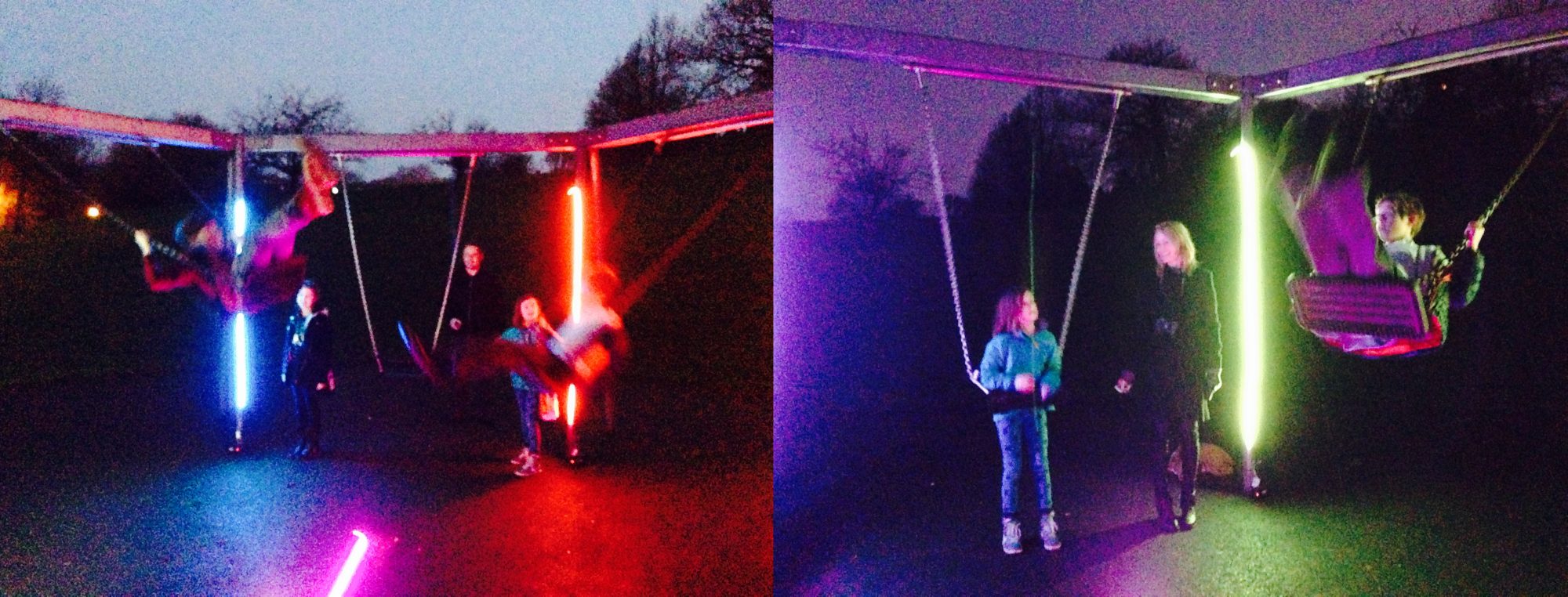

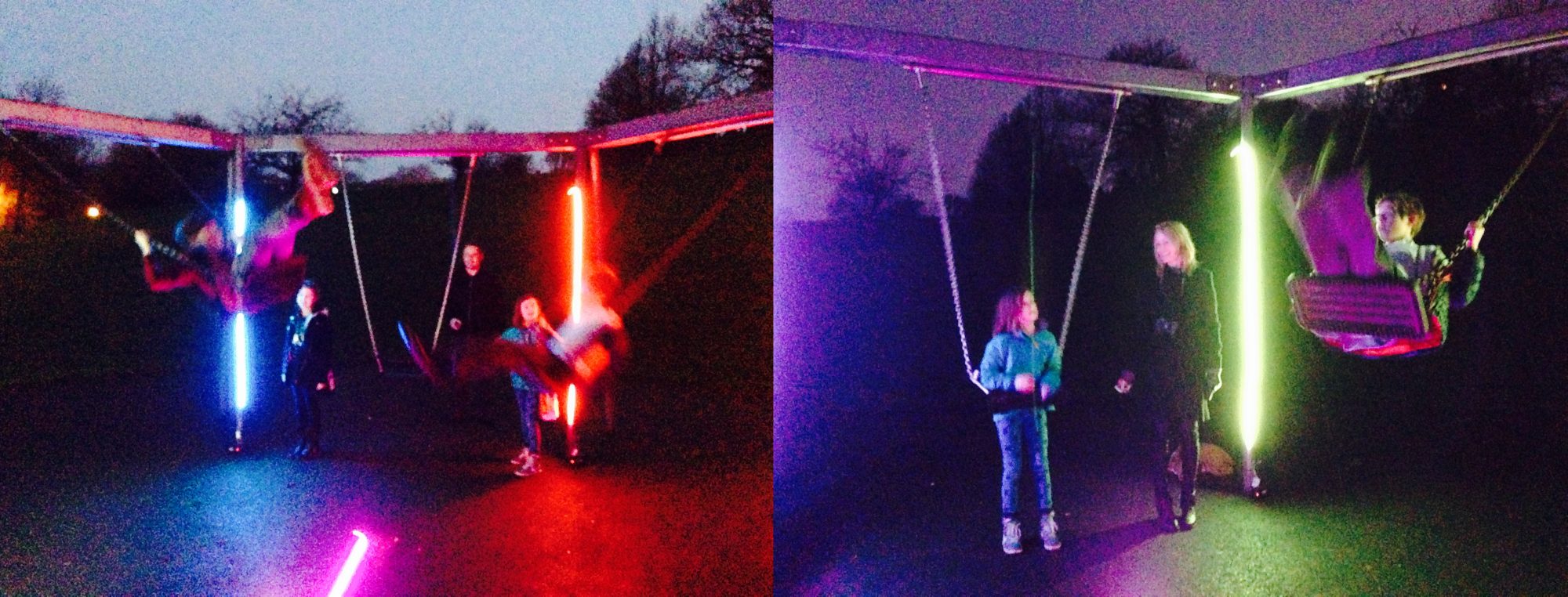

[For all the changes to children’s playground equipment from the Edwardian era to today], the proprioceptic and vertiginous pleasures of swinging and sliding persist, and children in playgrounds today are still largely climbing on, swinging through, and sliding down industrial forms and engineering. This kinaesthetic dynamic is not an eloquent or easily translatable language, but it does speak of a lived relationship with the mechanics of modernity that is at once absolutely tightly rivetted to industrial forms in material terms, but free-floating in the imaginary. The stories, characters and scenarios – or just free-floating chat, songs and jokes – may not appear to relate at all to the mining, smelting, forging and manufacturing of the steel infrastructure, but they are not arbitrary, no mere dreams. Rather they are generative of a diffuse and dispersed imaginary: embodied movement, scale, latitude in relation to the equipment itself, temporalities, repetitions (and rebellions) set to the rhythms of school life, meal-times, bedtimes that regulate children’s lives in the late modern era. How then might playground equipment be rethought and redesigned, adjusted or augmented for a postdigital era? Is its mechanical simplicity and ergonomic scaffolding of proprioceptive play essentially perfected now, separate from the industrial age in which it was forged and the mediated and virtualised play of the twenty-first century?

Extract from draft of ‘Playground equipment: postdigital design and the mechanics of history, space and play’ (under review).