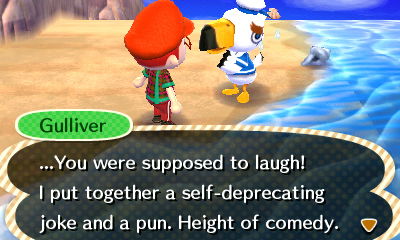

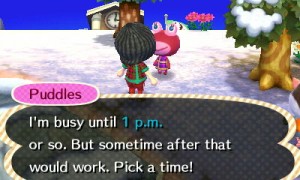

The clock and the world’s temporality in Animal Crossing are completely integral. The clock isn’t a measure of time, but virtual time’s arrow itself, driving forward the events, economies and relationships, not just ticking along beside them. The game has some elaborate measures built into its fiction to avoid temporal paradox, manipulation, or collapse. For example, in the 3DS version, Animal Crossing: new leaf, the player can buy turnips once a week from a boar called Joan. These can then be sold at a profit later in the week (the player must check the turnip prices each day – that is every actual day of the week – to determine the best time to sell). A player could quickly build up funds by repeatedly resetting the world’s clock to effectively “fast forward” from Joan’s arrival to the optimum market conditions. However the gameworld’s artificial-natural laws foreclose this market manipulation and, as Joan explains, if the clock is changed, the turnips immediately rot and cannot be sold. Animal Crossing’s temporality is integral to its social and economic systems too, which are in turn the basis of its gameplay: The game design intentionally draws on the passage of time to create both emotional resonance and economic value in the gameworld (Kelley 2007, 181-182).

The game is a virtual economy through which natural resources, commodities and affects flow. The player gathers natural resources for exchange for currency (“bells”): fruit, shells, insects, and fossils are shaken from trees, beach-combed, caught in a net, or dug out of the ground. Though the buying and selling of furniture, ornaments and natural resources in a series of little shops gives the impression of an economy of mercantile capitalism, it is in effect a simulation of pre-capitalist symbolic exchange in the anthropological sense. Rather than accumulation for its own sake, exchange here follows the logic of a gift economy (Mauss 2002 [1950], Baudrillard 1993). Animals ask a favour (to supply an apple or particular type of fish) and then reward the player with an object (an item of clothing, furniture or ornament), or they often respond to a visit or kind word from the player with a gift. Both pleasantries and objects flow between characters, cementing relationships and the virtual community. The bells accumulated by the player from these transactions are either fed back into the community through public works (park benches, bridges) or are spent on personal adornment or on enlarging and decorating the player’s house, in an odd mix of municipal socialism and potlatch performativity.

The circulation of affect is not constrained to the virtual world. Happy animals – who often sing and dance when especially pleased – delighted Jo and Alex, for example when the boys had remembered a character’s birthday (again in actual time, once a year) and visited its house with a present. Conversely, Jo once inadvertently opened a present he had been asked by one character to deliver to another and was upset almost to tears by the donor’s angry disapproval.

This is an economy primarily of affectual circulation – gift-giving, deliveries, writing and posting letters, short pre-rendered and often surreal conversations with non-player characters – the collusional flow and circulation of virtual objects initiating and sustaining relationships (and actual-world emotions) through exchange and gifts, flattery, the coining of new nicknames or characteristic greetings, delivery of presents for others, the finding of lost items. And gifts are – as anthropologist Marcel Mauss would approve – always reciprocated.

From Gameworlds: virtual media & children’s everyday play, New York: Bloomsbury. 2014.